Ensuring diagnostic performance of artificial intelligence (AI) before introduction into clinical practice is essential. Growing numbers of studies using AI for digital pathology have been reported over recent years. The aim of this work is to examine the diagnostic accuracy of AI in digital pathology images for any disease. This systematic review and meta-analysis included diagnostic accuracy studies using any type of AI applied to whole slide images (WSIs) for any disease. The reference standard was diagnosis by histopathological assessment and/or immunohistochemistry. Searches were conducted in PubMed, EMBASE and CENTRAL in June 2022. Risk of bias and concerns of applicability were assessed using the QUADAS-2 tool. Data extraction was conducted by two investigators and meta-analysis was performed using a bivariate random effects model, with additional subgroup analyses also performed. Of 2976 identified studies, 100 were included in the review and 48 in the meta-analysis. Studies were from a range of countries, including over 152,000 whole slide images (WSIs), representing many diseases. These studies reported a mean sensitivity of 96.3% (CI 94.1–97.7) and mean specificity of 93.3% (CI 90.5–95.4). There was heterogeneity in study design and 99% of studies identified for inclusion had at least one area at high or unclear risk of bias or applicability concerns. Details on selection of cases, division of model development and validation data and raw performance data were frequently ambiguous or missing. AI is reported as having high diagnostic accuracy in the reported areas but requires more rigorous evaluation of its performance.

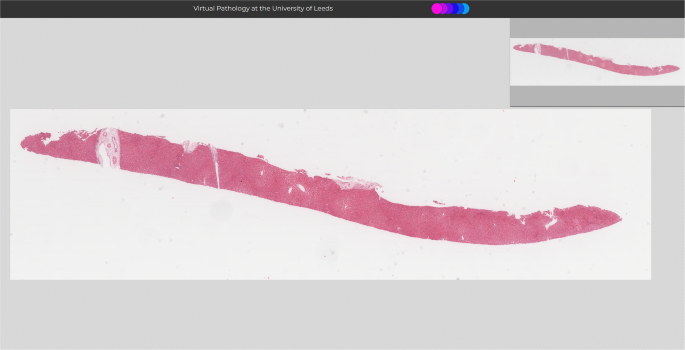

Following recent prominent discoveries in deep learning techniques, wider artificial intelligence (AI) applications have emerged for many sectors, including in healthcare 1,2,3 . Pathology AI is of broad importance in areas across medicine, with implications not only in diagnostics, but in cancer research, clinical trials and AI-enabled therapeutic targeting 4 . Access to digital pathology through scanning of whole slide images (WSIs) has facilitated greater interest in AI that can be applied to these images 5 . WSIs are created by scanning glass microscope slides to produce a high resolution digital image (Fig. 1), which is later reviewed by a pathologist to determine the diagnosis 6 . Opportunities for pathologists have arisen from this technology, including remote and flexible working, obtaining second opinions, easier collaboration and training, and applications in research, such as AI 5,6 .

Application of AI to an array of diagnostic tasks using WSIs has rapidly expanded in recent years 5,6,7,8 . Successes in AI for digital pathology can be found for many disease types, but particularly in examples applied to cancer 4,9,10,11 . An important early study in 2017 by Bejnordi et al. described 32 AI models developed for breast cancer detection in lymph nodes through the CAMELYON16 grand challenge. The best model achieved an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.994 (95% CI 0.983–0.999), demonstrating similar performance to the human in this controlled environment 12 . A study by Lu et al. in 2021 trained AI to predict tumour origin in cases of cancer of unknown primary (CUP) 13 . Their model achieved an AUC of 0.8 and 0.93 for top-1 and top-3 tumour accuracies respectively on an external test set. AI has also been applied to making predictions, such as determining the 5-year survival in colorectal cancer patients and the mutation status across multiple tumour types 14,15 .

Several reviews have examined the performance of AI in subspecialties of pathology. In 2020, Thakur et al. identified 30 studies of colorectal cancer for review with some demonstrating high diagnostic accuracy, although the overall scale of studies was small and limited in their clinical application 16 . Similarly in breast cancer, Krithiga et al. examined studies where image analysis techniques were used to detect, segment and classify disease, with reported accuracies ranging from 77 to 98% 17 . Other reviews have examined applications in liver pathology, skin pathology and kidney pathology with evidence of high diagnostic accuracy from some AI models 18,19,20 . Additionally, Rodriguez et al. performed a broader review of AI applied to WSIs and identified 26 studies for inclusion with a focus on slide level diagnosis 21 . They found substantial heterogeneity in the way performance metrics were presented and limitations in the ground truth used within studies. However, their study did not address other units of analysis and no meta-analysis was performed. Therefore, the present study is the first systematic review and meta-analysis to address the diagnostic accuracy of AI across all disease areas in digital pathology, and includes studies with multiple units of analysis.

Despite the many developments in pathology AI, examples of routine clinical use of these technologies remain rare and there are concerns around the performance, evidence quality and risk of bias for medical AI studies in general 22,23,24 . Although, in the face of an increasing pathology workforce crisis, the prospect of tools that can assist and automate tasks is appealing 25,26 . Challenging workflows and long waiting lists mean that substantial patient benefit could be realised if AI was successfully harnessed to assist in the pathology laboratory.

This systematic review provides an overview of performance of diagnostic tools across histopathology. The objective of this review was to determine the diagnostic test accuracy of artificial intelligence solutions applied to WSIs to diagnose disease. A further objective was to examine the risk of bias and applicability concerns within the papers. The aim of this was to provide context in terms of bias when examining the performance of different AI tools (Fig. 1).

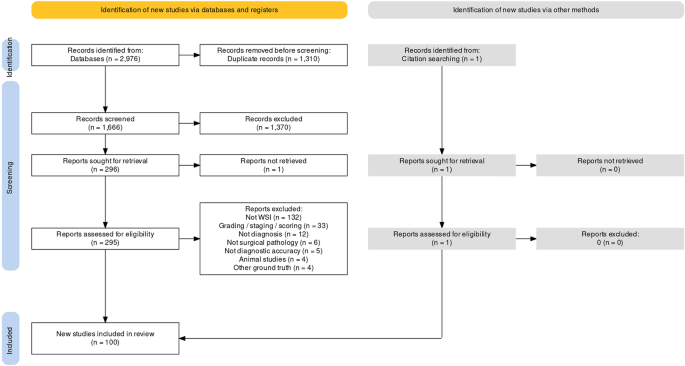

Searches identified 2976 abstracts, of which 1666 were screened after duplicates were removed. 296 full text papers were reviewed for potential inclusion. 100 studies met the full inclusion criteria for inclusion in the review, with 48 studies included in the full meta-analysis (Fig. 2).

Study characteristics are presented by pathological subspecialty for all 100 studies identified for inclusion in Tables 1–7. Studies from Europe, Asia, Africa, North America, South America and Australia/Oceania were all represented within the review, with the largest numbers of studies coming from the USA and China. Total numbers of images used across the datasets equated to over 152,000 WSIs. Further details, including funding sources for the studies can be found in Supplementary table 10. Tables 1 and 2 show characteristics for breast pathology and cardiothoracic pathology studies respectively. Tables 3 and 4 are characteristics for dermatopathology and hepatobiliary pathology studies respectively. Tables 5 and 6 have characteristics for gastrointestinal and urological pathology studies respectively. Finally, Table 7 outlines characteristics for studies with multiple pathologies examined together and for other pathologies such as gynaepathology, haematopathology, head and neck pathology, neuropathology, paediatric pathology, bone pathology and soft tissue pathology.

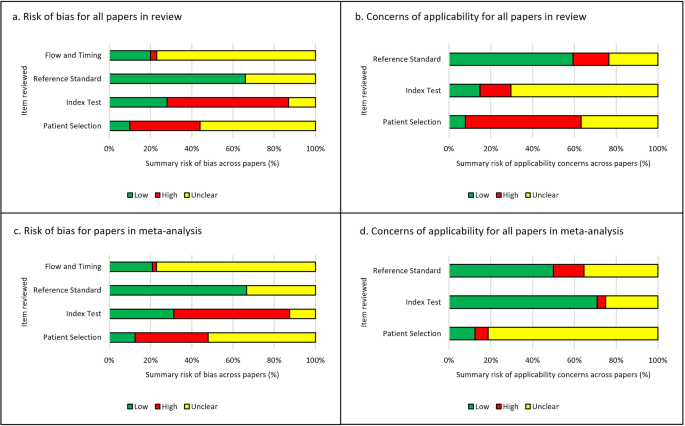

Of the 48 studies included in the meta-analysis (Fig. 3c, d), 47 of 48 studies (98%) were at high or unclear risk of bias or applicability concerns in at least one area examined. 42 of 48 studies (88%) were either at high or unclear risk of bias for patient selection and 33 of 48 studies (69%) were at high or unclear risk of bias concerning the index test. The most common reasons for this included: cases not being selected randomly or consecutively, or the selection method being unclear; the absence of external validation of the study’s findings; and a lack of clarity on whether training and testing data were mixed. 16 of 48 studies (33%) were unclear in terms of their risk of bias for the reference standard, but no studies were considered high risk in this domain. There was often very limited detail describing the reference standard, for example the process for classifying or diagnosing disease, and so it was difficult to assess if this was an appropriate reference standard to use. For flow and timing, to ensure cases were recent enough to the study to be relevant and reasonable quality, one study was at high risk but 37 of 48 studies (77%) were at unclear risk of bias.

There were concerns of applicability for many papers included in the meta-analysis with 42 of 48 studies (88%) with either unclear or high concerns for applicability in the patient selection, 14 of 48 studies (29%) with unclear or high concern for the index test and 24 of 48 studies (50%) with unclear or high concern for the reference standard. Examples for this included; ambiguity around the selection of cases and the risk of excluding subgroups, and limited or no details given around the diagnostic criteria and pathologist involvement when describing the ground truth.

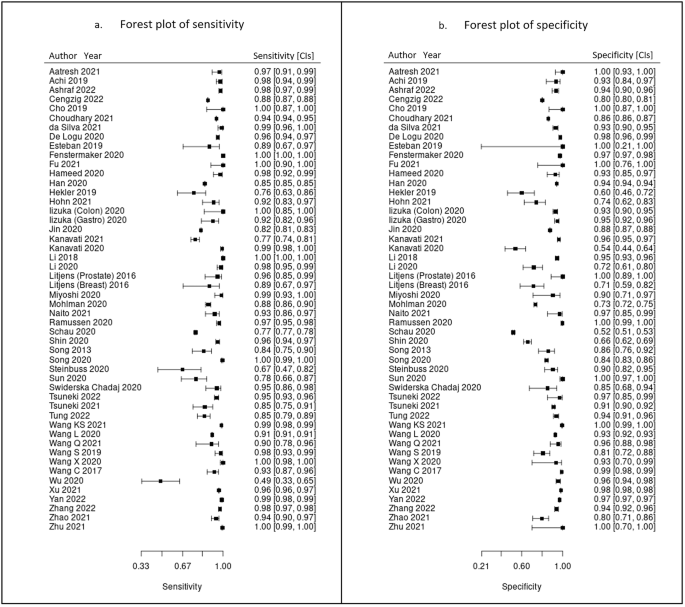

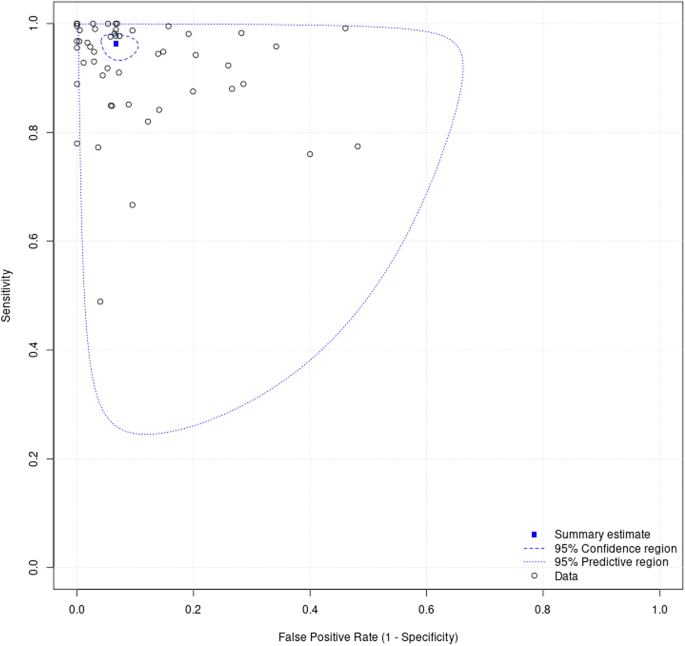

100 studies were identified for inclusion in this systematic review. Included study size varied greatly from 4 WSIs to nearly 30,000 WSIs. Data on a WSI level was frequently unavailable for numbers used in test sets, but where it was reported this ranged from 10 WSI to nearly 14,000 WSIs, with a mean of 822 WSIs and a median of 113 WSIs. The majority of studies had small datasets and just a few studies contained comparatively large datasets of thousands or tens of thousands of WSIs. Of included studies, 48 had data that could be meta-analysed. Two of the studies in the meta-analysis had available data for two different disease types 27,28 , meaning a total of 50 assessments included in the meta-analysis. Figure 4 shows the forest plots for sensitivity of any AI solution applied to whole slide images. Overall, there was high diagnostic accuracy across studies and disease types. Using a bivariate random effects model, the estimate of mean sensitivity across all studies was 96.3% (CI 94.1–97.7) and of mean specificity was 93.3% (CI 90.5–95.4), as shown in Fig. 5. Additionally, the F1 score was calculated for each study (Supplementary Materials) from the raw confusion matrix data and this ranged from 0.43 to 1, with a mean F1 score of 0.87. Raw data and additional data for the meta-analysis can be found in Supplementary Tables 3 and 4.

The largest subgroups of studies available for inclusion in the meta-analysis were studies of gastrointestinal pathology 28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40 , breast pathology 27,41,42,43,44,45,46,47 and urological pathology 27,48,49,50,51,52,53,54 which are shown in Table 8, representing over 60% of models included in the meta-analysis. Notably, studies of gastrointestinal pathology had a mean sensitivity of 93% and mean specificity of 94%. Similarly, studies of uropathology had mean sensitivities and specificities of 95% and 96% respectively. Studies of breast pathology had slightly lower performance at mean sensitivity of 83% and mean specificity of 88%. Results for all other disease types are also included in the meta-analysis 55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74 . Forest plots for these subgroups are shown in Supplementary figure 1. When examining cancer (48 of 50 models) versus for non-cancer diseases (2 of 50 models), performance was better for the former with mean sensitivity 92% and mean specificity 89% compared to mean sensitivity of 76% and mean specificity of 88% respectively. For studies that could not be included in the meta-analysis, an indication of best performance from other accuracy metrics provided is outlined in Supplementary Table 2.

Table 8 Mean performance across studies by pathological subspecialtyOf models examined in the meta-analysis, the number of sources ranged from one to fourteen and overall the mean sensitivity and specificity improved with a larger number of data sources included in the study. For example, mean sensitivity and specificity for one data source was 89% and 88% respectively, whereas for three data sources this was 93% and 92% respectively. However, the majority of studies used one or two data sources only, meaning that studies with larger numbers of data sources were comparably underrepresented. Additionally, of these models, the mean sensitivity and specificity was higher in those validated on an external test set (95% and 92% respectively compared to those without external validation (91% and 87% respectively), although it must be acknowledged that frequently raw data was only available for internal validation performance. Similar performance was reported across studies that had a slide-level and patch/tile-level unit of analysis with a mean sensitivity of 95% and 91% respectively versus a mean specificity of 88% and 90% respectively. When comparing tasks where data was provided in a multiclass confusion matrix compared to a binary confusion matrix, multiclass tasks demonstrated slightly better performance with a mean sensitivity of 95% and mean specificity of 92% compared to binary tasks with mean sensitivity 91% and mean specificity 88%. Details of these analyses can be found in Supplementary Tables 5–9.

Of papers included within the meta-analysis, details of specimen preparation were frequently not specified, despite this potentially impacting the quality of histopathological assessment and subsequent AI performance. In addition, the majority of models in the meta-analysis used haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) images only, with two models using H&E combined with IHC, making comparison of these two techniques difficult. Further details of these findings can be found in Supplementary Table 11.

AI has been extensively promoted as a useful tool that will transform medicine, with examples of innovation in clinical imaging, electronic health records (EHR), clinical decision making, genomics, wearables, drug development and robotics 75,76,77,78,79,80 . The potential of AI in digital pathology has been identified by many groups, with discoveries frequently emerging and attracting considerable interest 9,81 . Tools have not only been developed for diagnosis and prognostication, but also for predicting treatment response and genetic mutations from the H&E image alone 8,9,11 . Various models have now received regulatory approval for applications in pathology, with some examples being trialled in clinical settings 54,82 .

Despite the many interesting discoveries in pathology AI, translation to routine clinical use remains rare and there are many questions and challenges around the evidence quality, risk of bias and robustness of the medical AI tools in general 22,23,24,83,84 . This systematic review and meta-analysis addresses the diagnostic accuracy of AI models for detecting disease in digital pathology across all disease areas. It is a broad review of the performance of pathology AI, addresses the risk of bias in these studies, highlights the current gaps in evidence and also the deficiencies in reporting of research. Whilst the authors are not aware of a comparable systematic review and meta-analysis in pathology AI, Aggarwal et al. performed a similar review of deep learning in other (non-pathology) medical imaging types and found high diagnostic accuracy in ophthalmology imaging, respiratory imaging and breast imaging 75 . Whilst there are many exciting developments across medical imaging AI, ensuring that products are accurate and underpinned by robust evidence is essential for their future clinical utility and patient safety.

This study sought to determine the diagnostic test accuracy of artificial intelligence solutions applied to whole slide images to diagnose disease. Overall, the meta-analysis showed that AI has a high sensitivity and specificity for diagnostic tasks across a variety of disease types in whole slide images (Figs. 4 and 5). The F1 score (Supplementary Materials) was variable across the individual models included in the meta-analysis. However, on average there was good performance demonstrated by the mean F1 score. The performance of the models described in studies that were not included in the meta-analysis were also promising (see Supplementary Materials).

Subgroups of gastrointestinal pathology, breast pathology and urological pathology studies were examined in more detail, as these were the largest subsets of studies identified (see Table 8 and Supplementary Materials). The gastrointestinal subgroup demonstrated high mean sensitivity and specificity and included AI models for colorectal cancer 28,29,30,32,34,40 , gastric cancer 28,31,33,37,38,39,85 and gastritis 35 . The breast subgroup included only AI models for breast cancer applications, with Hameed et al. and Wang et al. demonstrating particularly high sensitivity (98%, 91% respectively) and specificity (93%, 96% respectively) 42,45 . However, there was lower diagnostic accuracy in the breast group compared to some other specialties. This could be due to several factors, including challenges with tasks in breast cancer itself, an over-estimation of performance and bias in other areas and the differences in datasets and selection of data between subspecialty areas. Overall results were most favourable for the subgroup of urological studies with both high mean sensitivity and specificity (Table 8). This subgroup included models for renal cancer 48,52 and prostate cancer 27,49,50,51,53,54 . Whilst high diagnostic accuracy was seen in other subspecialties (Table 8), for example mean sensitivity and specificity in neuropathology (100%, 95% respectively) and soft tissue and bone pathology (98%, 94% respectively), there were very few studies in these subgroups and so the larger subgroups are likely more representative.

Of studies of other disease types included in the meta-analysis (Fig. 4), AI models in liver cancer 74 , lymphoma 73 , melanoma 72 , pancreatic cancer 71 , brain cancer 67 lung cancer 57 and rhabdomyosarcoma 56 all demonstrated a high sensitivity and specificity. This emphasises the breadth of potential diagnostic tools for clinical applications with a high diagnostic accuracy in digital pathology. The majority of studies did not report details of the fixation and preparation of specimens used in the dataset. Where frozen section is used instead of formalin fixed paraffin embedded (FFPE) samples, this could impact the digital image quality and impact AI performance. It would be helpful for authors to consider including this information in the methods section of future studies. Only two models included in the meta-analysis used IHC and this was in combination with H&E stained samples. It would be interesting to explore the comparison between tasks using H&E when compared to IHC in more detail in future work.

Sensitivity and specificity were higher in studies with a greater number of included data sources, however few studies chose to include more than two sources of data. To develop AI models that can be applied in different institutions and populations, a diverse dataset is an important consideration for those conducting research into models intended for clinical use. A higher mean sensitivity and specificity for those models that included an external validation was identified, although many studies did not include this, or included most data for internal validation performance. Improved overall reporting of these values would allow a greater understanding of the performance of models at external validation. Performance was similar in the models included in the meta-analysis when a slide-level or patch/tile-level analysis was performed, although slide-level performance could be more useful when interpreting the clinical implications of a proposed model. A pathologist will review a case for diagnosis at slide level, rather than patch level, and so slide-level performance may be more informative when considering use in routine clinical practice. Performance was lower in non-cancer diseases when compared to cancer models, however only two of the models included in the meta-analysis were for non-cancer diseases and so this must be interpreted with caution and further work is needed in these disease areas.

Risk of bias and applicability assessments highlighted that the majority of papers contained at least one area of concern, with many studies having multiple areas of concern (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Materials). Poor reporting of the pieces of essential information within the studies was an issue that was identified at multiple points within this review. This was a key factor in the risk of bias and applicability assessment, as frequently important information that was either missing or ambiguous in its description. Reporting guidelines such as CLAIM and also STARD-AI (currently in development) are useful resources that could help authors to improve the completeness of reporting within their studies 29 , 86 . Greater endorsement and awareness of these guidelines could help to improve the completeness of reporting of this essential information in a study. The consequence of identifying so many studies with areas of concern, means that if the work were to be replicated with these concerns addressed, there is a risk that a lower diagnostic accuracy performance would be found. For this review, with 98–99% of studies containing areas of concern, any results for diagnostic accuracy need to be interpreted with caution. This is concerning due to the risk of undermining confidence of the use of AI tools if real world performance is poorer than expected. In future, greater transparency and reporting of the details of datasets, index test, reference standard and other areas highlighted could help to ameliorate these issues.

It must be acknowledged that there is uncertainty in the interpretation of the diagnostic accuracy of the AI models demonstrated in these studies. There was substantial heterogeneity in the study design, metrics used to demonstrate diagnostic accuracy, size of datasets, unit of analysis (e.g. slide, patch, pixel, specimen) and the level of detail given on the process and conduct of the studies. For instance, the total number of WSIs used in the studies for development and testing of AI models ranged from less than ten WSIs to tens of thousands of WSIs 87,88 . As discussed, of the 100 papers identified for inclusion in this review, 99% had at least one area at high or uncertain risk of bias or applicability concerns and similarly of the 48 papers included in the meta-analysis, 98% had at least one area at risk. Results for diagnostic accuracy in this paper should therefore be interpreted with caution.

Whilst 100 papers were identified, only 48 studies were included in the meta-analysis due to deficient reporting. Whilst the meta-analysis provided a useful indication of diagnostic accuracy across disease areas, data for true positive, false positive, false negative and true negative was frequently missing and therefore made the assessment more challenging. To address this problem, missing data was requested from authors. Where a multiclass study output was provided, this was combined into a 2 × 2 confusion matrix to reflect disease detection/diagnosis, however this offers a more limited indication of diagnostic accuracy. AI specific reporting guidelines for diagnostic accuracy should help to improve this problem in future 86 .

Diagnostic accuracy in many of the described studies was high. There is likely a risk of publication bias in the studies examined, with studies of similar models with lower reported performance on testing that are likely missing from the literature. AI research is especially at risk of this, given it is currently a fast moving and competitive area. Many studies either used datasets that were not randomly selection or representative of the general patient population, or were unclear in their description of case selection, meaning studies were at risk of selection bias. The majority of studies used either one or two data sources only and therefore the training and test datasets may have been comparatively similar. All of these factors should be considered when interpreting performance.

There are many promising applications for AI models in WSIs to assist the pathologist. This systematic review has outlined a high diagnostic accuracy for AI across multiple disease types. A larger body of evidence is available for gastrointestinal pathology, urological pathology and breast pathology. Many other disease areas are underrepresented and should be explored further in future. To improve the quality of future studies, reporting of sensitivity, specificity and raw data (true positives, false positives, false negatives, true negatives) for pathology AI models would help with transparency in comparing diagnostic performance between studies. Providing a clear outline of the breakdown of data and the data sources used in model development and testing would improve interpretation of results and transparency. Performing an external validation on data from an alternative source to that on which an AI model was trained, providing details on the process for case selection and using large, diverse datasets would help to reduce the risk of bias of these studies. Overall, better quality study design, transparency, reporting quality and addressing substantial areas of bias is needed to improve the evidence quality in pathology AI and to therefore harness the benefits of AI for patients and clinicians.

This systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted in accordance with the guidelines for the “Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses” extension for diagnostic accuracy studies (PRISMA-DTA) 89 . The protocol for this review is available https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID = CRD42022341864 (Registration: CRD42022341864).

Studies reporting the diagnostic accuracy of AI models applied to WSIs for any disease diagnosed through histopathological assessment and/or immunohistochemistry (IHC) were sought. This included both formalin fixed tissue and frozen sections. The primary outcome was the diagnostic accuracy of AI tools in detecting disease or classifying subtypes of disease. The index test was any AI model applied to WSIs. The reference standard was any diagnostic histopathological interpretation by a pathologist and/or immunohistochemistry.

Studies were excluded where the outcome was a prediction of patient outcomes, treatment response, molecular status, whilst having no detection or classification of disease. Studies of cytology, autopsy and forensics cases were excluded. Studies grading, staging or scoring disease, but without results for detection of disease or classification of disease subtypes were also excluded. Studies examining modalities other than whole slide imaging or studies where WSIs were mixed with other imaging formats were also excluded. Studies examining other techniques such as immunofluorescence were excluded.

Electronic searches of PubMed, EMBASE and CENTRAL were performed from inception to 20th June 2022. Searches were restricted to English language and human studies. There were no restrictions on the date of publication. The full search strategy is available in Supplementary Note 1. Citation checking was also conducted.

Two investigators (C.M. and H.F.A.) independently screened titles and abstracts against a predefined algorithm to select studies for full text review. The screening tool is available in Supplementary Note 2. Disagreement regarding study inclusion was resolved by discussion with a third investigator (D.T.). Full text articles were reviewed by two investigators (C.M. and E.L.C.) to determine studies for final inclusion.

Data collection for each study was performed independently by two reviewers using a predefined electronic data extraction spreadsheet. Every study was reviewed by the first investigator (C.M.) and a team of four investigators were used for second independent review (E.L.C./C.J./G.M./C.C.). Data extraction obtained the study demographics; disease examined; pathological subspecialty; type of AI; type of reference standard; datasets details; split into train/validate/test sets and test statistics to construct 2 × 2 tables of the number of true-positives (TP), false positives (FP), false negatives (FN) and true negatives (TN). An indication of best performance with any diagnostic accuracy metric provided was recorded for all studies. Corresponding authors of the primary research were contacted to obtain missing performance data for inclusion in the meta-analysis.

At the time of writing, the QUADAS-AI tool was still in development and so could not be utilised 90 . Therefore, a tailored QUADAS-2 tool was used to assess the risk of bias and any applicability concerns for the included studies 86,91 . Further details of the quality assessment process can be found in Supplementary Note 3.

Data analysis was performed using MetaDTA: Diagnostic Test Accuracy Meta-Analysis v2.01 Shiny App to generate forest plots, summary receiver operating characteristic (SROC) plots and summary sensitivities and specificities, using a bivariate random effects model 92,93 . If available, 2 × 2 tables were used to include studies in the meta-analysis to provide an indication of diagnostic accuracy demonstrated in the study. Where unavailable, this data was requested from authors or calculated from other metrics provided. For multiclass tasks where only multiclass data was available, the data was combined into a 2 × 2 confusion matrix (positives and negatives) format to allow inclusion in the meta-analysis. If negative results categories were unavailable for multiclass tasks, (e.g. for multiple comparisons between disease types only) then these had to be excluded. Additionally, mean sensitivity and specificity were examined in the largest pathological subspecialty groups, for cancer vs non-cancer diagnoses and for multiclass vs binary tasks to compare diagnostic accuracy among these studies.

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

C.M., C.J., G.M. and D.T. are funded by the National Pathology Imaging Co-operative (NPIC). NPIC (project no. 104687) is supported by a £50 m investment from the Data to Early Diagnosis and Precision Medicine strand of the Government’s Industrial Strategy Challenge Fund, managed and delivered by UK Research and Innovation (UKRI). E.L.C. is supported by the Medical Research Council (MR/S001530/1) and the Alan Turing Insititute. C.C. is supported by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Leeds Biomedical Research Centre. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care. H.F.-A. is supported by the EXSEL Scholarship Programme at the University of Leeds. We thank the authors who kindly provided additional data for the meta-analysis.