This month marks the 50th anniversary of the effective date of the Age Discrimination in Employment Act (the ADEA) -- one of the premier statutes enforced by the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC).

When I first joined the EEOC in April 2010, the job market was very different than it is today. The effects of the Great Recession were still being widely felt throughout the economy, and predictions were that it would take the nation 10 years or more to recover from steep job losses. At the EEOC, we were concerned that these job losses would hit older workers particularly hard.

Accordingly, shortly after I joined the Commission, one of the first public Commission meetings we held in November 2010, was about the "Impact of the Economy on Older Workers."

Fast forward to today, and as of this month, the nation is experiencing its lowest unemployment rate in 18 years. Instead of shedding hundreds of thousands of jobs each month, the economy is gaining them. This is very good news for America's workers.

But consider this: older workers who lose a job have much more difficulty finding a new job than younger workers. A 54-year-old worker who may have lost his job in early 2008 at the beginning of the Great Recession is now 64 years old. The average unemployment duration for a 54-year-old was almost a year, and it may have taken that person two or three years to find a new job. Further, that new job may not have been on a par with the one he had before. To make up for that financial loss, he will likely need to work longer than originally planned.

Now consider a 54-year-old worker who loses her job in today's economy. Today, jobs are plentiful and conditions are much more favorable for finding new jobs compared to 10 years ago. But, there is one constant for today's 54-year-old and the one from 10 years ago -- age discrimination.

As experts testified at the EEOC's meeting in June 2017 on The ADEA @ 50 -- More Relevant Than Ever, age discrimination remains a significant and costly problem for workers, their families, and our economy.

A few additional points for your consideration. Today's Baby Boomers range in age from 54 to 72 and because of that nearly 20-year span in age, they have widely different considerations about work and retirement. While about 10,000 Baby Boomers retire every day, many have inadequate savings for retirement. Work life has changed dramatically since Boomers entered the workforce. Instead of a career spanning one industry and a few positions as was expected at the beginning of their careers, most workers today are expected to have 11 different jobs in the modern, dynamic economy. Right behind the Boomers, the leading edge of Generation X are now in their early 50's. And, in 2016, Millennials surpassed the Baby Boomers as the largest segment of the workforce in 2016.

The scene having now been set, I offer this report, marking the 50th anniversary of when the ADEA took effect, culminating a year-long recognition by the EEOC of the importance of the ADEA as a significant civil rights law. While it is not exhaustive (as there are treatises devoted to the ADEA, after all), it is meant to serve as a guide to the history and significant developments of the law.

I hope the report also serves to put to rest outdated assumptions about older workers (who should more aptly be described as "experienced workers") and about age discrimination, which harm workers, their families and our economy. Today's experienced workers are healthier, more educated, and working and living longer than previous generations. Age-diverse teams and workforces can improve employee engagement, performance, and productivity. Experienced workers have talent that our economy cannot afford to waste.

I want to thank the staff at the EEOC for their contributions to this report, especially Cathy Ventrell-Monsees, whose passion for all things ADEA is priceless (and perhaps ageless).

Victoria A. Lipnic

Acting Chair

U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission

In 1967, Congress enacted the federal Age Discrimination in Employment Act (ADEA) to prohibit age discrimination in the workplace and promote the employment of older workers. The ADEA was an integral part of congressional actions in the 1960s to ensure equal opportunity in the workplace,[1] along with the Equal Pay Act of 1963[2] and the Civil Rights Act of 1964.[3] Together, these laws transformed the workplace by breaking down barriers to opportunity and building foundations of equality and fairness.

In passing the ADEA, Congress recognized that age discrimination was caused primarily by unfounded assumptions that age impacted ability.[4] To prevent and stop such arbitrary discrimination, the ADEA requires employers to consider individual ability, rather than assumptions about age, in making an employment decision.

A few years after the ADEA was enacted, the Senate Special Committee on Aging noted that the "ADEA was enacted, not only to enforce the law, but to provide the facts that would help change attitudes."[5] It was commonly assumed that at some age and in some jobs, age limited the abilities of older workers.[6] Today we ask: have attitudes about older workers, their abilities, and age discrimination changed in the wake of the ADEA over the past 50 years? Have employment practices changed to promote the employment of older workers?

This report examines the current state of age discrimination and older workers in the U.S. 50 years after the ADEA took effect in June 1968. It begins with a brief review of the history of the ADEA and its enforcement by the Department of Labor (DOL) and the EEOC. It describes the significant changes in who the older worker of today is compared to the typical older worker of 1967.Today's older workers are more diverse and more educated than previous generations. They are healthier and working and living longer. The women and men confronting age discrimination today are in all parts of our country -- in rural and urban communities, in blue and white-collar jobs, in service and tech industries, and are of all races, ethnicities and income.

Despite these dramatic changes, today's older workers still confront unfounded and outdated assumptions about age and ability and age discrimination persists.[7] Despite decades of research finding that age does not predict ability or performance, employers often fall back on precisely the ageist stereotypes the ADEA was enacted to prohibit.[8]After 50 years of a federal law whose purpose is to promote the employment of older workers based on ability, age discrimination remains too common and too accepted. Indeed, 6 out of 10 older workers have seen or experienced age discrimination in the workplace and 90 percent of those say it is common.[9]

This report acknowledges the significant harm and costs to older workers, their families, and employers that age discrimination causes. It is time to put to rest outdated and unfounded assumptions about age, older workers, and discrimination. Changing practices can help change attitudes. Thisreport concludes with promising practices for employers to not only avoid age discrimination, but to recognize the value of a multi-generational workforce. Simply put, our economy cannot afford to waste the knowledge, talent, and experience of older workers.[10]

Congress considered prohibiting age discrimination in employment as part of the Equal Employment Opportunity Act of 1962[11] and Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, but amendments to include age as a protected characteristic failed.[12] Instead, as part of Title VII, Congress directed the Secretary of Labor to make a "full and complete study of the factors which may tend to result in discrimination in employment because of age."[13] That report, "The Older American Worker, Age Discrimination in Employment,"[14] which became known as the "Wirtz Report" (after W. Willard Wirtz, then-Secretary of Labor) provided the foundation for the ADEA.

The Wirtz Report examined the nature, scope, and consequences of age discrimination in the workplace of the 1960s. It found that employers believed age impacted ability. It also found that without any factual basis or consideration of individual abilities, employers routinely barred workers in their 40s, 50s, and 60s from a wide range of jobs.[15]

The Wirtz Report contrasted this finding that age discrimination derived mostly from unfounded assumptions about ability with its finding that discrimination based on race, national origin and religion derived from "dislike and hostility" - specifically "feelings about people entirely unrelated to their ability to do the job."[16] These findings led the Wirtz Report to characterize age discrimination as "different" from discrimination based on race, color, religion or national origin,[17] and recommended against adding age to Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.[18]

The Wirtz Report found that one-half of employers used age limits to deny jobs to workers age 45 and older.[19] It found vast differences in perceptions of age and physical ability with some employers refusing to hire workers after age 25 and others hiring workers until age 60 for jobs involving comparable physical capabilities.[20]

The Wirtz Report also examined factors such as health, education, technology and "institutional arrangements" such as personnel policies, seniority systems, and benefit plans that may impact older worker employment.[21] Studies relating to health and age noted that older workers had fewer acute health issues than younger workers.[22] However, because older workers were more susceptible to chronic conditions, they were more likely to be rejected for employment even though such conditions wouldn't prevent them from working.[23] Educational levels of older workers in the 1960s significantly impacted their employment prospects, as three-fifths of those age 55 and older had less than a high school degree.[24] Technological changes at the time caused the displacement of traditional industries and geographic dislocation, and resulted in young workplaces in new industries where the hiring of older workers would be viewed as "exceptional."[25]

Finally, the Wirtz Report considered the significant consequences of age discrimination on older workers, which it described as hardship and frustration, and on the economy with billion dollar costs in unemployment and early Social Security payouts, plus lost production and earnings.[26] The Report concluded with recommendations for a national policy against arbitrary discrimination in employment on the basis of age, actions to modify institutional arrangements that disadvantaged older workers, and actions to increase the hiring of older workers.[27]

President Lyndon B. Johnson proposed legislation based in part on the Wirtz Report.[28] Amendments to the Administration's bill by the leading proponents of a federal age discrimination bill, notably Senator Jacob Javits and Senator Ralph Yarborough,[29] led to the enactment of the ADEA on December 15, 1967.[30] The legislation took effect on June 12, 1968.[31]

Recognizing the challenge of changing both employment practices and attitudes about age and ability,[32] Congress set forth ambitious purposes for the ADEA:

It is therefore the purpose of this chapter to promote employment of older persons based on their ability rather than age; to prohibit arbitrary age discrimination in employment; to help employers and workers find ways of meeting problems arising from the impact of age on employment.[33]

Congress crafted a statute based on provisions from both Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA).[34] The ADEA shares Title VII's purpose to eliminate discrimination from the workplace.[35] The ADEA's prohibitions were taken verbatim from Title VII,[36] as was its narrow exception for the use of age as a bona fide occupational qualification (BFOQ).[37] Courts interpret this language from Title VII, including its prohibitions and the BFOQ exception, to apply with "equal force" to the ADEA's substantive provisions.[38] The remedies of the ADEA, by contrast, flow from the FLSA. When initially enacted, Congress limited ADEA coverage to individuals age 40 to 64[39] and again directed the Secretary of Labor to study the ages protected by the statute.[40]

In its first decade, the ADEA was expanded to cover federal, state and local government employees.[42] Congress sought to provide older workers with the same basic civil rights as other workers.[43]

With each significant amendment to the ADEA, Congress laid out the scientific evidence refuting any assumed correlation between age and ability.[44] At the same time, however, the early versions of the ADEA essentially fostered the belief that age affected ability by capping the age of coverage -- initially at 65, and then at age 70 in 1978.[45] These age caps on coverage permitted employers to deny jobs to the oldest workers and to force workers to retire based solely on age.[46] Congress finally resolved this tension in the 1986 amendments to the ADEA, which removed the age-70 cap on coverage.[47] Congress supported removal of the age-70 cap with both scientific[48] and public opinion evidence for the fact that age is not predictive of job-related ability or performance.[49]

The most extensive revisions to the ADEA occurred in 1990 when Congress enacted the Older Workers Benefit Protection Act of 1990 (OWBPA)[50] in response to the Supreme Court's decision in Public Employees Retirement System of Ohio v. Betts.[51] The OWBPA amended the ADEA to restore its original congressional intent to prohibit age discrimination in employee benefits,[52] and established new minimum standards for voluntary waivers and releases of ADEA claims or rights.[53]

Congress initially debated what entity should have enforcement authority for the ADEA.[54] Congress expressed concerns that the newly formed EEOC had a substantial backlog of charges after only two years in existence and deemed the agency under-resourced to handle responsibility for another discrimination statute.[55] Congress decided that the existing enforcement staff in the Department of Labor's Wage and Hour Division[56]would provide the most effective enforcement of the ADEA and thus granted enforcement authority to DOL.[57]

DOL promptly issued regulations in 1968 under the ADEA that explicitly rejected the use of age-related assumptions about physical ability.[58]In its first full year of enforcing the ADEA, DOL investigated over one thousand complaints of age discrimination.[59]In a 1972 report to Congress just three years later, DOL had found violations of the ADEA in 36 percent of its 6,000 investigations in 1972.[60] In its first few years of ADEA enforcement, DOL filed over 80 lawsuits under the ADEA with 30 successful resolutions.[61]

Early in 1978, the Carter Administration recognized that fragmented enforcement of the nation's civil rights laws had impeded their effectiveness and resulted in "regulatory duplication and needless expense for employers."[62] In particular, the overlap in those covered by Title VII and the ADEA was considered "burdensome to employers and confusing to victims of discrimination."[63] With the goal of a "unified, coherent Federal structure to combat discrimination in all its forms," the Carter Administration transferred enforcement of the ADEA to the EEOC with congressional approval, effective January 1, 1979.[64]

When the EEOC assumed responsibility for enforcement of the ADEA in 1979, the EEOC had to overcome many challenges,[65]such as different charge processing procedures from DOL, an increase in ADEA charge filings, and a lack of adequate training and resources.[66] At the same time, the EEOC was already dealing with a backlog of over 100,000 Title VII charges.[67] The challenges that the EEOC faced in the early years of ADEA enforcement[68]led to difficulties in the timely investigations of ADEA charges, requiring two amendments to extend the statute of limitations for filing a lawsuit.[69]

Despite these challenges, the EEOC's litigation docket of ADEA cases grew rapidly in the first few years after it was granted the authority to bring them.[70] About one-quarter of EEOC's ADEA cases challenged maximum hiring and mandatory retirement ages for police and firefighters.[71] In these cases, the EEOC successfully defeated constitutional challenges to the ADEA's application to state government employers.[72] ADEA suits against state government employers continue to be a significant part of the EEOC's litigation program,[73]particularly since the Supreme Court eliminated the right of private individuals to seek damages in such suits.[74]

Throughout the history of its ADEA litigation program, many of the EEOC's major ADEA cases focused on discriminatory reductions-in-force, denial of benefits, and mandatory retirement policies.[75] In the past decade, the EEOC has also focused on challenging discriminatory hiring policies, both individual[76]and systemic.[77]

Under its authority to issue substantive ADEA regulations,[78]the EEOC has issued regulations detailing requirements for waivers under the OWPBA,[79]exempting retiree health benefits from ADEA coverage,[80]clarifying that the ADEA does not prohibit employers from favoring older workers,[81]and explaining the reasonable factor other than age affirmative defense.[82]

The workforce of 1967 looked very different than it does today. Men worked most of their careers for one company or in one profession and retired at early ages with pensions.[83] Just over one-third of workers were women.[84] Average life expectancy was 67 for men and 74 for women.[85] Many jobs were physically demanding. Members of the leading edge of the Baby Boom, those born between 1946 and 1964,[86]were just entering the work force in 1967.

Today's US labor force has doubled in size,[87] and is older, more diverse, more educated, and more female than it was 50 years ago.[88]

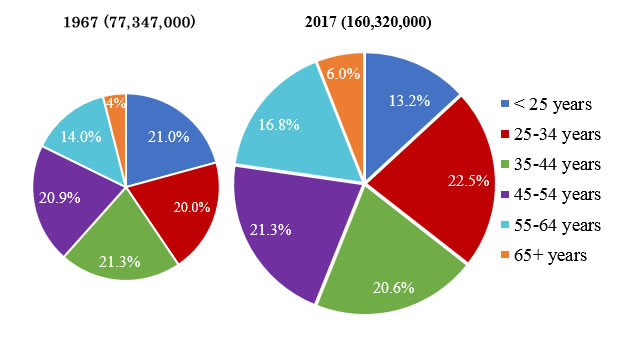

Age of Civilian US Labor Force (Chart 1) :

These trends are expected to continue for decades.[89] One of the most notable changes in the American workforce over the past 50 years is that it has aged significantly with the aging of the Baby Boom generation (79 million people) over that time.[90]

The most dramatic changes in the age of the labor force occurred in the last 25 years, as the share of workers age 55 and older in the workforce doubled.[91] In recent years, workers age 65 and older are staying in or re-entering the workforce in greater numbers. The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) estimates that the oldest segments of the workforce -- those ages 65 to 74 and 75 and older -- are expected to increase the fastest through 2024.[92] This oldest cohort of workers of age 65+ workers is projected to grow by 75 percent by 2050, while the group of workers age 25 to 54 is only expected to grow by 2 percent over this same period.[93]

Increased labor force participation by older women is a significant factor in this growth of the older workforce. Women age 55 and older are projected to make up over 25 percent of the women's labor force by 2024, which is almost double their share from 2000. BLS also forecasts that twice as many women over 55 will be in the labor force as women ages 16-24 by 2024. BLS also estimates that women over 65 will make up roughly the same percentage of the female workforce as older men do of the male workforce.[94]

People are working longer today than their parents and grandparents did for a variety of reasons.[95] This generation of older workers is generally healthier and has longer life expectancy than previous generations.[96] In addition, eligibility for full Social Security benefits starts at later ages[97] and the demise of traditional pension benefits provided by employers has shifted greater responsibility to individuals for their retirement income.[98] Now, less than half of the private sector workforce age 25 to 64 have an employer-sponsored plan of any type.[99]

The Great Recession of 2007-2009 [100](also known as the Great Dislocation[101]) forced many older workers to revise their retirement plans and to work longer to recoup drained retirement accounts and lost savings. It left many older workers less confident that they would have sufficient income for a comfortable retirement.[102] As a result, the Great Recession flipped retirement plans and expectations for older workers. [103] Prior to 2009, most Americans planned to retire before age 65.[104] Since then, most say they will retire after age 65.[105]

Unfortunately, retirement expectations frequently do not pan out. For example, one study reports that while 40 percent of workers planned to work until age 70 or later, only 4 percent actually do.[106] Unexpected events such as ill health, caregiving responsibilities, getting laid off, and age discrimination can thwart the best-laid plans.

In addition, the concept of "retirement" has changed markedly with the Baby Boom generation. Retirement traditionally meant the end of paid employment. Today, retirement can also mean continued employment in another role, job or career.[107] Many retirees also must work,[108] even if those opportunities pay less than their previous jobs.[109] Many others work in "retirement" for personal fulfillment as well as financial security.[110]

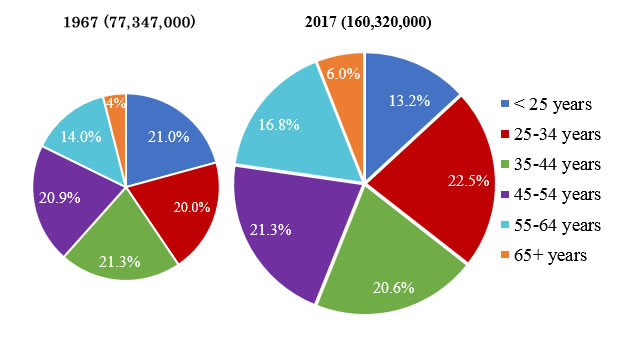

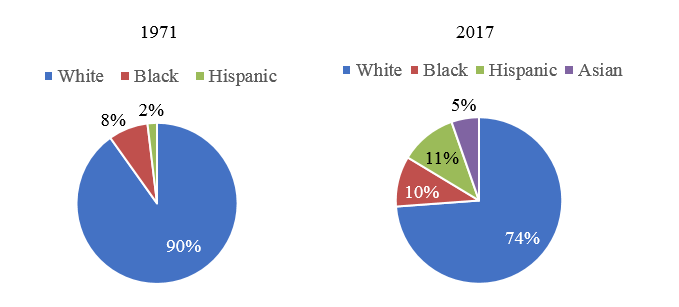

Both the age and diversity of the US workforce has increased considerably over the past decades and will continue to increase in the coming decade.[111] Since 2000,the participation rate of both women and men age 55 and older in each of the four-major race[112] and ethnicity groups increased.[113] As indicated in Charts 2 and 3, the percentage of older workers who are Hispanic significantly increased over the past five decades. The proportion of Hispanics age 55 to 64 in the workforce jumped from 2 percent in 1971 to 11 percent in 2017. Hispanics workers also continued working past age 65 at increasing rates, from 1 percent in 1971 to 8 percent in 2017. The percentage of the labor force age 55 and older consisting of racial and ethnic minorities has grown substantially and is expected to continue to do so into the next decade.[114]

Change in Racial/Ethnic Composition of Labor Force Participants

Ages 55-64, 1971 - 2017 (Chart 2)[115]

Change in Racial/Ethnic Composition of Labor Force Participants

Ages 65+, 1971 - 2017 (Chart 3)

The 1965 Wirtz Report noted that older workers were more likely to be employed in coal mining, agriculture, and railroads, and in older manufacturing industries such as textiles, leather, apparel, footwear, and food.[116] Today, workers ages 55 and older are employed across many types of occupations.[117] More than 42 percent of older workers are in management, professional, and related occupations, a somewhat higher proportion than that for all workers.[118] Thirty-six percent of older workers are engaged in blue collar work.[119] Workers age 65 and older are in part-time jobs at more than double the rate of younger workers, but they are increasingly seeking and obtaining full-time employment.[120] Finally, an increasing number of older workers are self-employed; the rate of self-employment is much higher for older than for younger workers.[121]

The five most common jobs for men and women age 62 and older are:[122]

| Men | Women | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Top occupations | % of older workers | Top occupations | % of older workers |

| Delivery workers and truck drivers | 3.95 | Teachers, except postsecondary | 6.30 |

| Janitors and building cleaners | 2.99 | Secretaries and administrative assistants | 6.04 |

| Farmers and ranchers | 2.58 | Personal care aides | 3.60 |

| Postsecondary teachers | 2.39 | Registered nurses | 3.45 |

| Lawyers | 2.37 | Child care workers | 3.36 |

Notably, many of the most common jobs held by older workers require a college education (e.g., teachers, lawyers, nurses), and/or are physically demanding (e.g., delivery workers, janitors, aides, and nurses.) [123]

Today, it is estimated that about 44 percent of older workers are employed in jobs with some physical demands or difficult working conditions.[124] The extent of physical demands in a job can vary considerably. For example, only about seven percent of all American workers and six percent of older workers hold highly physically demanding jobs, and this number is projected to decline to about five percent by 2041.[125]

To put this dramatic change of the physical demands of jobs into historical context, many of the jobs held by older workers in the 1960s were in manufacturing, mining, agriculture, and railroads and were highly physically demanding. As these industries contracted and as technology has changed how work gets done over the past fifty years, the total percentage of all workers employed in physically demanding jobs has steadily decreased.[126] Across all industries, jobs requiring some form of physical activity fell from 57 percent in 1971 to 46 percent in 2006.[127]

Discrimination today, whether based on age, race, sex or other protected characteristics, frequently derives from stereotypes and unconscious bias,[128] although blatant or explicit discriminatory practices still exist.

Unfounded assumptions about age and ability continue to drive age discrimination in the workplace. Research on ageist stereotypes demonstrates that most people have specific negative beliefs about aging and that most of those beliefs are inaccurate.[129] These stereotypes often may be applied to older workers, leading to negative evaluations[130] and/or firing, rather than coaching or retraining.[131]

Given the dramatic changes in our understanding of aging, work, and discrimination, it is time to put aside such outdated assumptions about aging and age discrimination; the ADEA was intended and continues to be an important tool to do just that.

Decades of social science research document that age does not predict one's ability, performance, or interest.[132] Aging and its effect on cognitive abilities is highly individualized, as ability, agility and creativity vary widely among people of the same age.[133] Many older people out-perform or perform as well as young people,[134] and intellectual functions can actually improve with age.[135] While speedy thinking may decline over time, middle-aged brains adapt to reach solutions faster, make sounder judgments, and better navigate the complex world of today.[136] Innovation and creativity span the age spectrum as well.[137]

Physical ability also varies considerably from person to person and from one age to another age. While everyone experiences changes in physical functioning as they age, the extent and effects of aging on an individual's physical ability vary considerably from one person to another and are dependent on genetics, lifestyle, fitness, and health status.[138] If a job requires physical fitness standards,[139] it is common to provide ranges of both age and gender norms in tests to assess physical capacity.[140]

The notion that age discrimination is different than other forms of discrimination because of different historical origins is a central premise of the Wirtz Report and continues to seep into ADEA jurisprudence today. For example, even recently, a judge questioned a plaintiff's evidence of age discrimination by saying:

No, age is different because we are all going to get old … but when you're talking about gender or race or ethnicity those are immutable characteristics as the Supreme Court has said. But it's a little bit different because all of us are going to be older or elderly one day.[141]

When examined through today's understanding of how discrimination operates, age discrimination is more like, than different from, other forms of discrimination.

First, as a legal matter, Congress made irrelevant the view of the Wirtz Report that age discrimination was different by using the same words to prohibit age discrimination as it used in Title VII to prohibit discrimination based on race, sex, color, national origin, and religion.[142] Congress clearly viewed employment discrimination as a unified phenomenon suited to a unified legislative solution, regardless of whether the protected characteristic was age, race, sex, or another basis protected by Title VII.

Second, all employment discrimination shares prejudices about the competence of members of the protected group. For example, race discrimination unquestionably originated from a long history of malice, prejudice and intolerance. Yet, race discrimination also derives from negative views and stereotypes about the abilities of workers of a particular race,[143] like age discrimination does.

Third, when one compares age to sex discrimination, there are again important similarities. There is substantial evidence that in the 1960s, people believed that one's gender determined one's abilities, interests and qualifications,[144] just like age. Sex discrimination, like age discrimination, often results from stereotypes about women's abilities and on assumptions about the appropriate roles of women in the workplace and society.[145]

In sum, age discrimination shares a commonality with other forms of discrimination, just as the ADEA and Title VII share common purposes and prohibitions. Thus, this notion that age discrimination is "different" should not justify less protection for older workers in interpreting the ADEA.

It is difficult to measure with any accuracy the prevalence of discrimination in the workplace. One indicator of the prevalence of age discrimination is based on research of the perception of age discrimination by older workers in surveys. Another indicator is age discrimination claims. Most discriminatory and harassing conduct is unreported,[146] which means charges filed with federal and state enforcement agencies represent a fraction of the likely discrimination that occurs in the workplace.

The perception that age discrimination exists in our workplaces is prevalent. More than 6 in 10 workers age 45 and older say they have seen or experienced age discrimination in the workplace.[147] Of those, 90 percent say it is somewhat or very common, according to a 2017 survey.[148] In another survey in 2015, more than 3 of 4 older workers said their age was an obstacle to finding a job.[149]

African Americans/Blacks report much higher rates of having experienced age discrimination or knowing someone who had, at 77 percent, compared to 61 percent for Hispanics/Latinos and 59 percent for Whites.[150] More women than men also say older workers face age discrimination.[151]

Older workers in the technology industry report significantly high rates of age discrimination, with 70 percent of those on IT staffs reporting they had witnessed or experienced age discrimination.[152] More than 40 percent of older tech workers are worried about losing their jobs because of age[153]or consider their age to be a liability to their career.[154]

Older workers facing age discrimination can file ADEA charges with the EEOC or with state and local Fair Employment Practice agencies. While most older workers say they have seen or experienced age discrimination, only 3 percent report having made a formal complaint to someone in the workplace or to a government agency.[155] This suggests vast underreporting of the problem of age discrimination.

In the first years of ADEA enforcement, yearly charge filings with DOL ranged from just over 1,000 to over 5,000.[156] The EEOC assumed responsibility for the ADEA in 1979, ADEA charges jumped most significantly in 1983,[157] increasing by 67 percent from the previous year, which was also two times the percentage increase of other types of charge filings in 1983.[158] ADEA charges filed with the EEOC reached an all-time high of 24,582 in fiscal year 2008.[159]

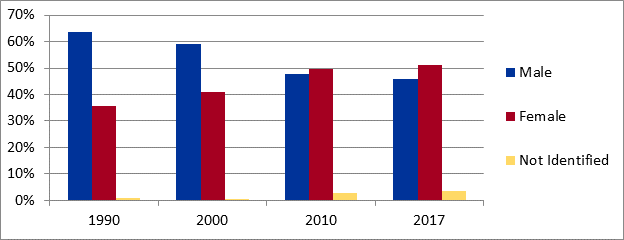

The demographics of older workers who file ADEA charges have changed markedly since 1967. The most dramatic change is in the gender of those filing ADEA charges, as depicted in Chart 4 below. In 1990, almost twice as many ADEA charges were filed by men than were filed by women. In 2010, the number of women filing age charges surpassed the number of men filing age charges for the first time, a trend that continues today.

ADEA Charges by Gender (Chart 4)

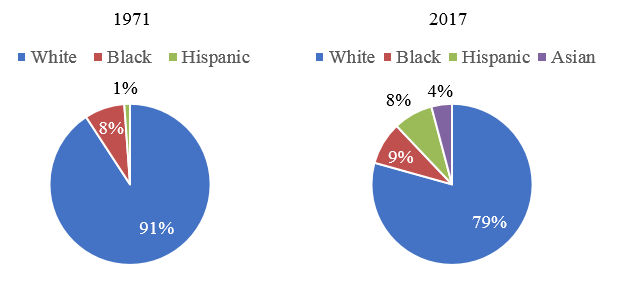

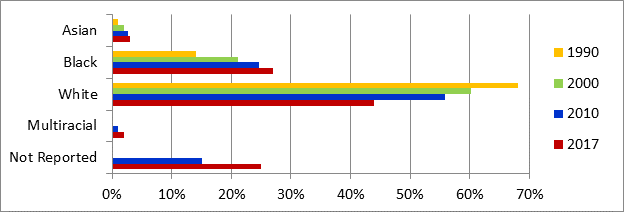

With each passing decade, the racial diversity of those who file age discrimination charges also is growing (Chart 5). The percentages of charges alleging age discrimination filed by Blacks[160] and Asians[161] doubled by 2017 compared to 1990 charge filings. The percentage of ADEA charges filed by Whites declined by over one third (from 68 percent to 42 percent).

ADEA Charges by Race (Chart 5)

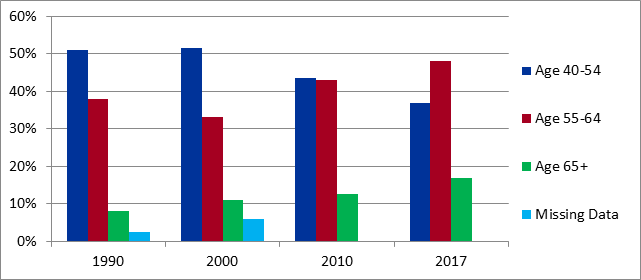

Additionally, the age of those filing ADEA charges has changed dramatically (Chart 6). In 1990, workers in the age 40-54 age cohort filed the majority of ADEA charges and workers in the age 65+ cohort filed relatively few. But by 2017, more charges were filed by workers ages 55-64 than the younger age cohort. Moreover, by 2017, the percentage of charges filed by workers age 65 and older was double what it was in 1990.

ADEA Charges by Age Group (Chart 6)

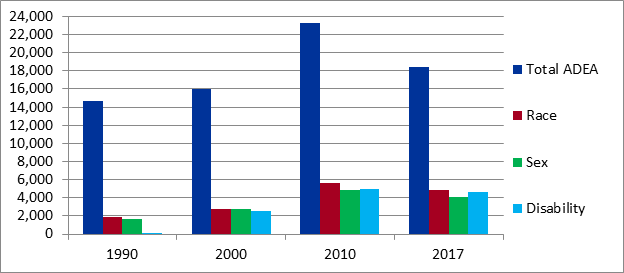

The percentage of charges alleging age discrimination plus race, sex or disability has also increased dramatically over the past 20 years as the older workforce has become more diverse. (Chart 7).

ADEA Charges Alleging Age and Race, Age and Sex, Age and Disability Discrimination (Chart 7)

While the ADEA has eliminated or changed many employment practices that explicitly used age to bar opportunities to older workers, discriminatory practices continue today to deny older workers equal opportunity. Research shows that older workers' continued denial of equal opportunity often derives from negative stereotypes.[162] Indeed, there is strong "evidence that age bias and negative age stereotypes about older workers continue to affect older workers' employment experiences."[163]

Unlawful discharge has always been the most common practice asserted in charges filed with the EEOC[164] and that remains true for ADEA charges as well. In fiscal year 2017, 55 percent of ADEA charges alleged discriminatory discharge. Twenty-five years ago, about 45 percent of ADEA charges claimed unlawful discharge. ADEA lawsuits alleging unlawful discharge based on age, including constructive discharge, based on age have similarly dominated ADEA litigation, with one study finding discharges raised in 73 percent of ADEA district court and appellate court cases.[165]

The next most common allegations in ADEA charges have varied over the years. Age-based harassment claims more than tripled by 2017 to 21 percent, compared to 6 percent in 1992. The types of harassment experienced by older workers is often like that experienced by other workers.[166] ADEA charges raising claims of discriminatory terms or conditions nearly doubled to 25 percent in 2017 from 13 percent in 1992. Finally, allegations of discriminatory discipline nearly quintupled to 11.6 percent in 2017 from only 2.5 percent in 1992.

As previously discussed, many older workers report that their age is an obstacle to getting a job.[167] The extent of age discrimination in hiring has been documented in resume-correspondence studies conducted over the past two decades that compare interview rates of older and younger applicants.[168] These studies find substantial evidence of age discrimination in hiring, as most hiring discrimination occurs when an interview is offered or not.[169]

The largest and most recent field study of age discrimination in hiring was conducted in 2015 and involved over 40,000 applications for over 13,000 jobs in 12 cities across 11 states.[170] It found evidence of age discrimination against both men and women, with older applicants - those age 64 to 66 years old -- more frequently denied job interviews than middle-age applicants age 49 to 51.[171] Women, especially older women but also those at middle age, were subjected to more age discrimination than older men.[172]

At an EEOC meeting on Promoting Diverse and Inclusive Workplaces in the Tech Sector, the EEOC heard from experts about micro-targeting practices seeking to recruit younger workers. Experts also testified about job postings preferring younger workers as "digital natives," rather than older workers who are referred to as "digital immigrants." [173] They also testified about online application systems that include dates of birth or graduation dates in fields that cannot be bypassed. Such practices may deter and disadvantage older applicants.

Challenges to mandatory retirement policies and the discriminatory denial of benefits dominated the early decades of ADEA litigation. The Supreme Court issued unanimous decisions in three cases in 1985, ruling for the older workers who challenged practices related to mandatory retirement policies.[174] The EEOC successfully eliminated numerous policies that forced the retirement of police, firefighters, and other public safety officers.[175] Congress, however, later amended the ADEA to allow state and local governments to impose mandatory retirement for police and firefighters in limited circumstances.[176]

The legality of early retirement incentives[177] and pension plans[178] that denied or reduced benefits based on age have been frequent claims in ADEA litigation. After the Supreme Court held that the ADEA did not generally prohibit discrimination in employee benefit plans in Public Employees Retirement System v. Betts,[179] Congress enacted the OWBPA[180] to make clear that the ADEA prohibits an employer from denying or reducing benefits based on age, except in specific circumstances sanctioned by the OWBPA.[181]

The ADEA was initially construed to protect retiree health benefits and prohibit the use of Medicare eligibility to determine benefits for retirees in Erie County RetireesAss 'n v. County of Erie, Pennsylvania.[182] Based on concerns that employer-sponsored health benefits would be dropped in their entirety unless employers could use Medicare-eligibility to determine their availability, the EEOC issued a regulatory exemption from the ADEA permitting the coordination of retiree health benefits with Medicare or a comparable state health benefit plan.[183]

The EEOC has long recognized the theory of "intersectional discrimination"[184] under both Title VII[185] and the ADEA[186] when an individual is treated differently because he or she belongs to more than one protected category and is subjected to a set of stereotyping unique to his or her status. The availability of an intersectional claim has become increasingly important for older women as more of them experience both age and sex discrimination.[187]

The financial and emotional harm of age discrimination on older workers and their families is significant. Once an older worker loses a job, she will likely endure the longest period of unemployment compared to other age groups and will likely take a significant pay cut if she becomes re-employed.[188] The loss of a job has serious long-term financial consequences as older workers often must draw down their retirement savings while unemployed, and are likely to suffer substantial losses in income if they become re-employed.[189]

The emotional harm of any discrimination is traumatic.[190] For older workers, they typically feel betrayed when they have given many years of their working lives to one employer.[191] Research shows that perceived age discrimination results in serious negative health effects, in part, because with advancing age, older individuals are exposed to more negative ageist stereotypes that make them feel older than their chronological age.[192] Forced retirement correlates with significant declines in mental and physical health that can lead to shortened life spans.[193]

Age discrimination also has significant monetary costs for employers. Lawsuits can impose substantial costs for employers for violating the ADEA,[194]which just a few examples demonstrate. The largest ADEA suit to date, Arnett v. California Public Employees' Retirement System,[195] settled for $250,000,000, and a permanent injunction against the state pension system and 1,500 local agencies, for reducing the disability pension benefits of police and firefighters based on age. Sprint Nextel settled an ADEA collective action for $57.5 million for 1700 older workers laid off between 2001 and 2003.[196] An age discrimination lawsuit brought by 129 older workers at the Livermore National Laboratory settled for $37.5 million in 2015.[197]

EEOC resolved lawsuits involving mandatory retirement policies against Johnson & Higgins for $28.1 million and Sidley and Austin for $27.5 million. 3M resolved three-related ADEA lawsuits for $15 million and significant organizational changes and monitoring by EEOC in 2011.[198] Recent EEOC cases challenging age discrimination in hiring against Texas Roadhouse settled for $12 million[199] and against Seasons 52 for $2.85 million.[200]

When Congress was considering the ADEA in 1967, 24 states and Puerto Rico had laws prohibiting age discrimination in the workplace.[201] A majority of those state laws included a prohibition against age discrimination within an omnibus anti-discrimination law that also prohibited discrimination based on race, color, religion, national origin, and sex.[202] Rather than follow the predominant model used by the states that would add age to Title VII, Congress chose to create a separate federal law, the ADEA.

Today, every state except South Dakota has a law prohibiting age discrimination in the workplace. Forty-three state laws[203] include age within their omnibus anti-discrimination laws, meaning the same standards and damages apply in age cases as they do in other state law discrimination cases.[204] Thirty-two state laws provide for either compensatory and/or punitive damages, with 21 states providing for both. Given the availability of greater damages than the federal ADEA permits and higher success rates in state courts,[205] older workers in these states frequently pursue claims only under state law or under both state and federal law.[206]

Experts have testified before the EEOC expressing concerns about Supreme Court decisions in the past decade and a half that have severed the ADEA from its ties to Title VII, by relying on textual differences between the ADEA and Title VII, rather than their shared purposes and prohibitions.[207] The most significant ADEA case that experts point to that divorces the ADEA from Title VII precedent is Gross v. FBL Financial Services, Inc.[208] Gross held that older workers could no longer use the motivating factor framework derived from the same Title VII prohibition[209] shared by the ADEA to prove unlawful age discrimination. Instead, the Supreme Court reasoned that the 1991 addition to Title VII of a provision setting forth a motivating factor framework did not apply to the ADEA because Congress failed to similarly amend the ADEA.[210]

Thus, while individuals with race or sex discrimination claims under Title VII can prove unlawful disparate treatment under either a "but for" causation standard or a "motivating factor" standard, victims of age discrimination are limited to just one -- a "but for" standard.[211] And even though the Supreme Court said in Gross that there is no heightened standard to prove age discrimination,[212] some courts have interpreted Gross as making ADEA cases harder to prove.[213] This can be extremely problematic for older women and older minorities who often bring claims under both the ADEA and Title VII.[214]

Too many older Americans continue to face discrimination based on persistent stereotypes and outdated assumptions about age and work. Age discrimination is legally wrong and has been since the ADEA took effect five decades ago. But it remains too common and too accepted in today's workplace. While attitudes about older workers, their abilities, and age discrimination have improved somewhat over the past 50 years, much more can and should be done to make age discrimination less prevalent and less accepted.

What more can be done to fulfill the ADEA's promise that ability matters, not age? Research shows that stereotypes are tenacious and it takes generations to change a stereotype.[215] Workplace practices, however, can counter unconscious bias and stereotyping.[216] Changing practices rather than trying to just change attitudes to eliminate bias can produce real and sustainable benefits for both employees and employers.[217]

First and foremost, workplace culture determines whether workers are valued without regard to age or whether they are devalued based on age.[218] The leadership of an organization is obviously critical to creating and fostering a culture that is committed to a multi-generational workplace where all workers can grow and thrive.[219] Workplace cultures that extol ability and reject discriminatory stereotypes and words result in more diverse, productive and engaged workforces.

Second, employers and employees can also help prevent age discrimination in the workplace by recognizing and rejecting stereotypes, assumptions, and remarks about age and older workers just as they reject such stereotypes, assumptions and remarks about someone's sex, race, disability, national origin, or religion.

In addition, the following strategies were recommended by experts at EEOC meetings to avoid age discrimination, increase age diversity in the workplace, and value a multi-generational workforce.

Based on research studies and their work with employers, experts recommend several strategies that can prevent biases from entering into recruitment, hiring, and human resource practices. One significant but often overlooked strategy is to include age in diversity and inclusion programs and efforts. A study by PriceWaterhouseCoopers found that 64 percent of firms surveyed in its 2015 Annual Global CEO survey had diversity & inclusion strategies, but only 8 percent of those included age.[220] Yet, the benefits of doing so appear to have strong positive outcomes for both employers and employees.

Research demonstrates that age diversity can improve organizational performance and lower employee turnover.[221] Studies also find that mixed-age work teams result in higher productivity for both older and younger workers.[222] Older workers who report their companies have a high "Workplace Diversity Focus" have the highest levels of employee satisfaction.[223]

An initial assessment of an organization's culture, practices, and policies may reveal outdated assumptions about older workers that could taint objective decision-making and limit opportunities. The Center on Aging & Work at Boston College, along with AARP, has developed an assessment tool that evaluates organizational strengths and weaknesses in attracting, managing, and retaining a multigenerational workforce.[224]

With low unemployment and growing shortages of skilled, qualified workers, hiring older workers can help employers fill what has become known as the "skills gap" -- the lack of trained or experienced workers for higher-skilled jobs. Their employment also furthers economic and social policies that encourage continued work to strengthen personal financial well-being and our economy.[225]

Recruitment practices can avoid age bias by seeking workers of all ages and not limiting qualifications based on age or years of experience. Over 94 percent of working Americans visit companies' social media pages when searching for a job.[226] Websites and social media that include age-diverse photos, graphics, and content demonstrate a commitment to attracting a multi-generational workforce. Applications, whether online or paper, should not ask date of birth or other age-related questions, just as they should not ask an applicant to identify her race or sex.

Training recruiters and interviewers to avoid ageist assumptions and even common perceptions about older workers is critical. For example, the assumption that hiring a younger worker is less expensive and a better return on investment than hiring an older worker is outdated and flawed. Contrary to common perception, older workers do not cost significantly more than younger workers, as structural changes in compensation and benefits have created a more age-neutral distribution of labor costs.[227] And the presumed investment based on the assumption that the younger worker will be with the employer longer is less likely these days. Millennials are leaving their employers, on average, after three years, whereas older workers, on average, provide employers with more stability, longer tenures, and ultimately a greater return on investment.[228]

Experts also recommend an assessment of interviewing strategies to avoid age bias, as studies and experience show that interviewers tend to favor job candidates who remind them of themselves.[229] An age-diverse interview panel for prospective employees may be viewed more positively by candidates and may be less vulnerable to implicit bias. Training interviewers as to how to frame age-neutral questions and using a standard or structured process can help avoid age bias throughout the interview process.[230]

Effective retention strategies decrease unexpected turnover costs and loss of institutional knowledge, and increase engagement and productivity. Age is positively correlated with employee engagement, as workers age 50 and older have the highest levels of engagement in the workplace.[231] And high employee engagement increases employee productivity.[232]

Experts recommend strategies to provide career counseling, training and development opportunities to workers at all ages and at all stages of their careers. Mixed-age and reverse-age mentoring can increase worker productivity and satisfaction.[233] Workers of all ages value flexible work options that can provide work/life balance at various times in their careers.[234]

The ADEA has helped to bring equality and fairness to the workplace for older workers. But age discrimination persists based on outdated and unfounded assumptions about older workers, aging and discrimination. No one should be denied a job based on stereotypes and it's time to put these outdated assumptions to rest. Ability, experience and commitment matter, not age. To achieve the promise of the ADEA, it's time to recognize the value of age diversity in the workplace and the benefits of a multi-generational workforce.

[1] "The ADEA, enacted in 1967 as part of an ongoing congressional effort to eradicate discrimination in the workplace, reflects a societal condemnation of invidious bias in employment decisions. The ADEA is but part of a wider statutory scheme to protect employees in the workplace nationwide. See Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964." McKennon v. Nashville Banner Publ'g Co., 513 U.S. 352, 357-58 (1995) (citations omitted).

[2] Pub. L. 88-38, 77 Stat. 56 (1963) (codified at 29 U.S.C. § 206(d)).

[3] Pub. L. No. 88-352, 78 Stat. 241, 253-66 (1964) (codified at 42 U.S.C. § 2000e et seq.).

[5] Improving the Age Discrimination Law, A Working Paper, S. Spec. Comm. On Aging, 93 Cong. 1st Sess. III (1973).

[6] Wirtz Report, supra note 4 at 21.

[7] Department of Labor, Employment and Training Administration, Report of the Taskforce on the Aging of the American Workforce, 20 (2008).

[8] Daniel Kohrman & Mark Hayes, Employers Who Cry "RIF" and the Courts That Believe Them, 23 Hofstra Lab. & Emp. L.J. 153 (2005) (showing that bias against older people is more deeply embedded than other forms of bias including race, gender, religion, and sexual orientation).

[9] Rebecca Perron, The Value of Experience: Age Discrimination Against Older Workers Persists, AARP (forthcoming 2018) (study conducted in September 2017 of 3,900 of those aged 45 and older either working or looking for work).

[10] "If more skilled workers over 60 stayed in the workforce, it would make a significant impact on reducing the skilled worker shortage in the United States." Written Testimony of John Challenger, CEO, Challenger, Gray & Christmas, Inc., The ADEA 50 -- More Relevant Than Ever, Meeting of the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (2017).

[11] H.R. 10144 sought to prohibit "arbitrary employment discrimination because of race, religion, color, national origin, ancestry or age." H.R. Rep. No. 97-1370, 97th Cong. 2d Sess. 2155 (1962).

[12] The amendment to add a prohibition of age discrimination to Title VII failed in the House by a vote of 123 to 94. 110 Cong.Rec. 2596-99 (1964).The Senate rejected a similar amendmentby a vote of 63 to 28. 110 Cong.Rec. 9911-13 (1964). Some ADEA historians claim that the move to add age discrimination to TitleVII was intended to defeat passage, like the move to add sex discrimination. See Daniel P. O'Meara, Protecting The Growing Numbers of Older Workers: The Age Discrimination in Employment Act 11 (1989) ; Disparate Impact Analysis and the Age Discrimination in Employment Act, 64 Minn. L. Rev. 1038, 1053 (1984); Alfred W. Blumrosen, Interpreting the ADEA: Intent or Impact, Age Discrimination in Employment Act: A Compliance and Litigation Manual for Lawyers and Personnel Practitioners, 106-15 (1982). Historians also disagree on the reasons Congress added sex to Title VII. J. Freeman, How Sex Got into Title VII: Persistent Opportunism as A Maker of Public Policy, 9 Law and Inequality: A Journal of Theory and Practice, 163-184 (1991); M.E. Gold, A Tale of Two Amendments: The Reasons Congress Added Sex to Title VII and Their Implication for The Issue of Comparable Worth, 19 Duquesne Law Rev. 453-477 (1980).

[13] Civil Rights Act of 1964 , Pub. L. No. 88-352, § 715, 78 Stat. 265 (1964).

[14] Wirtz Report, supra note 4.

[15] "Physical capability is by far the most prominent single reason advanced for imposing upper age limits." Id. at 8.

[17] Id. at 6. The Wirtz Report did not compare the origins or motives driving sex discrimination to the motivations for age discrimination.

[19] The 1965 Wirtz Report included a study of over 500 employers, and found that 3 out of 5 employers surveyed used age limits in hiring. Workers age 45 and older were barred from a quarter of all jobs, those 55 and older were barred from half of all jobs, and most jobs were barred to workers age 65 and older. Seventy percent of those employers surveyed who barred older workers from a wide variety of jobs reported no factual basis for the age cutoff they selected, while other employers hired and retained older workers for the same jobs at the same ages for which these employers barred them. Id. at 8.